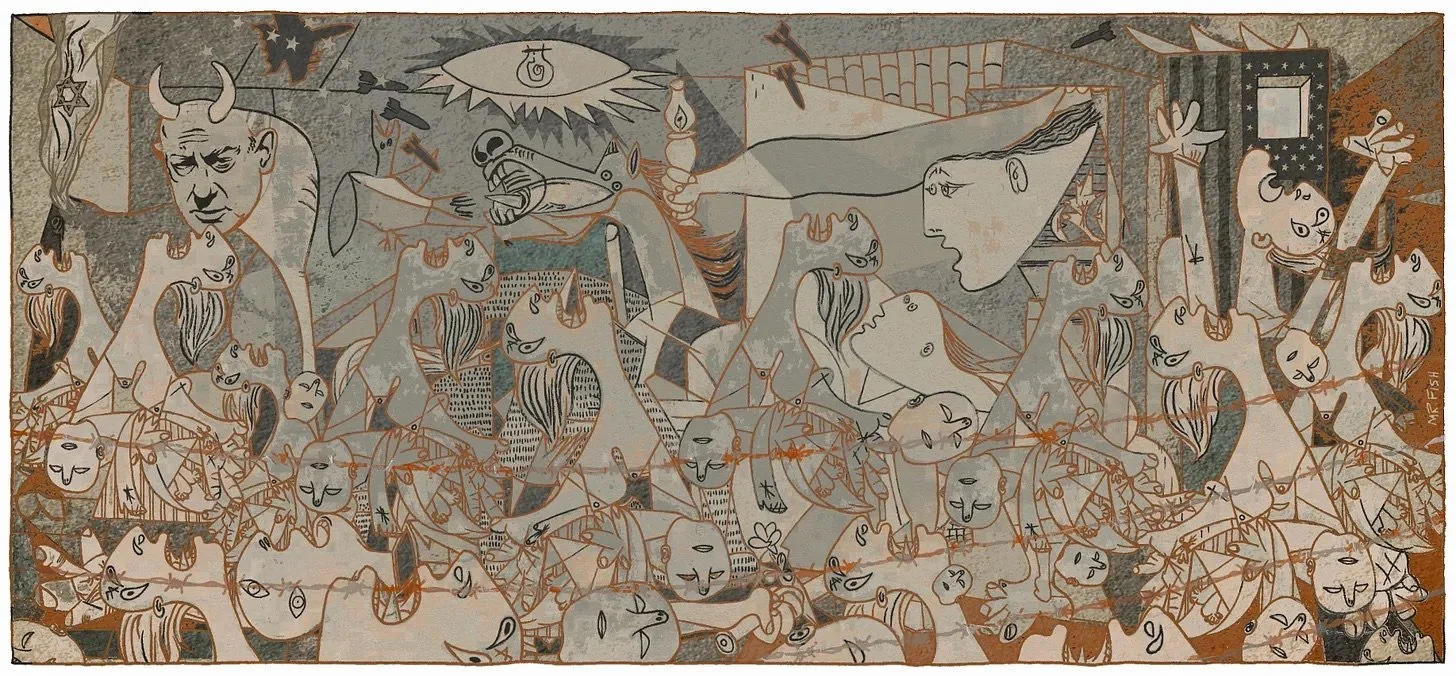

The Old Evil

Which Genocide Are You On? - by Mr. Fish

I returned to occupied Palestine, from where I had reported for The New York Times, after two decades. I experienced once more the visceral evil of Israel’s occupation.

by CHRIS HEDGES

RAMALLAH, Occupied Palestine: It comes back in a rush, the stench of raw sewage, the groan of the diesel, sloth-like Israeli armored personnel carriers, the vans filled with broods of children, driven by chalky faced colonists, certainly not from here, probably from Brooklyn or somewhere in Russia or maybe Britain. Little has changed. The checkpoints with their blue and white Israeli flags dot the roads and intersections. The red-tiled roofs of the colonist settlements — illegal under international law — dominate hillsides above Palestinian villages and towns. They have grown in number and expanded in size. But they remain protected by blast barriers, concertina wire and watchtowers surrounded by the obscenity of lawns and gardens. The colonists have access to bountiful sources of water in this arid landscape that the Palestinians are denied.

The winding 26-foot high concrete wall that runs the 440 mile length of occupied Palestine, with its graffiti calling for liberation, murals with the Al-Aqsa mosque, faces of martyrs and the grinning and bearded mug of Yasser Arafat — whose concessions to Israel in the Oslo agreement made him, in the words of Edward Said, “the Pétain of the Palestinians” — give the West Bank the feel of an open air prison. The wall lacerates the landscape. It twists and turns like some huge, fossilized antediluvian snake severing Palestinians from their families, slicing Palestinian villages in half, cutting communities off from their orchards, olive trees and fields, dipping and rising out of wadis, trapping Palestinians in the Jewish state’s updated version of a Bantustan.

It has been over two decades since I reported from the West Bank. Time collapses. The smells, sensations, emotions and images, the lilting cadence of Arabic and the miasma of sudden and violent death that lurks in the air, evokes the old evil. It is as if I never left.

I am in a battered black Mercedes driven by a friend in his thirties who I will not name to protect him. He worked construction in Israel but lost his job — like nearly all Palestinians employed in Israel — on Oct. 7. He has four children. He is struggling. His savings have dwindled. It is getting hard to buy food, pay for electricity, water and petrol. He feels under siege. He is under siege. He has little use for the quisling Palestinian Authority. He dislikes Hamas. He has Jewish friends. He speaks Hebrew. The siege is grinding him, and everyone around him, down.

“A few more months like this and we’re finished,” he says puffing nervously on a cigarette. “People are desperate. More and more are going hungry.”

We are driving the winding road that hugs the barren sand and scrub hillsides snaking up from Jericho, rising from the salt-rich Dead Sea, the lowest spot on the earth, to Ramallah. I will meet my friend, the novelist Atef Abu Saif, who was in Gaza on Oct. 7 with his 15-year-old son, Yasser. They were visiting family when Israel began its scorched earth campaign. He spent 85 days enduring and writing daily about the nightmare of the genocide. His collection of haunting diary entries have been published in his book “Don’t Look Left.” He escaped the carnage though the border with Egypt at Rafah, traveled to Jordan and returned home to Ramallah. But the scars of the genocide remain. Yasser rarely leaves his room. He does not engage with his friends. Fear, trauma and hatred are the primary commodities imparted by the colonizers to the colonized.

“I still live in Gaza,” Atef tells me later. “I am not out. Yasser still hears bombing. He still sees corpses. He does not eat meat. Red meat reminds him of the flesh he picked up when he joined the rescue parties during the massacre in Jabalia, and the flesh of his cousins. I sleep on a mattress on the floor as I did in Gaza when we lived in a tent. I lie awake. I think of those we left behind waiting for sudden death.”

We turn a corner on a hillside. Cars and trucks are veering spasmodically to the right and left. Several in front of us are in reverse. Ahead is an Israeli checkpoint with thick boxy blocks of dun colored concrete. Soldiers are stopping vehicles and checking papers. Palestinians can wait hours to get past. They can be hauled from their vehicles and detained. Anything is possible at an Israeli checkpoint, often erected with no advance warning. Most of it is not good.

We back up. We descend a narrow, dusty road that veers off from the main highway. We travel on bumpy, uneven tracks through impoverished villages.

It was like this for Blacks in the segregated south and Indigenous Americans. It was like this for Algerians under the French. It was like this in India, Ireland and Kenya under the British. The death mask — too often of European extraction — of colonialism does not change. Nor does the God-like authority of colonists who look at the colonized as vermin, who take a perverse delight in their humiliation and suffering and who kill them with impunity.

The Israeli customs official asked me two questions when I crossed into occupied Palestine from Jordan on the King Hussein Bridge.

“Do you hold a Palestinian passport?”

“Are either of your parents Palestinian?”

In short, are you contaminated?

This is how apartheid works.

The Palestinians want their land back. Then they will talk of peace. The Israelis want peace, but demand Palestinian land. And that, in three short sentences, is the intractable nature of this conflict.