The Redneck Army Refuses to Stay Buried

Triangle Rock, a swimming hole on the North Fork of the South Branch of the Potomac River. Photographs by Aaron Blum.

By Cassady Rosenblum

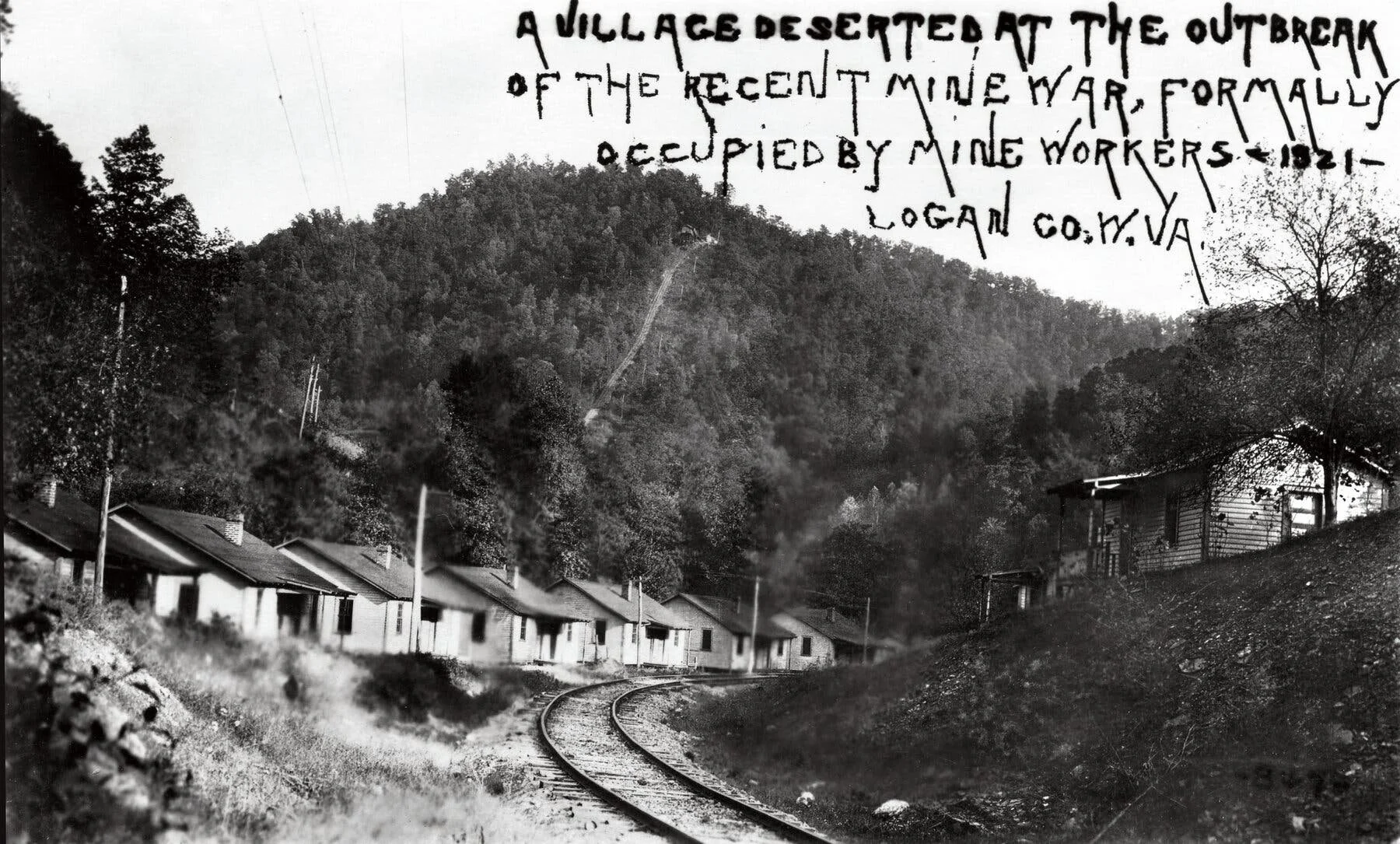

The striking miners were 10,000 strong on the first day of September 1921 as they charged up the slope of Blair Mountain, propelled by a radical faith in the American dream. According to an Associated Press reporter who crouched behind a log and watched through field glasses, each time they pressed forward, a “veritable wall” of machine gun fire drove them back. As the barrage echoed through the hollows, reminding some of the action they had just seen in the forests of France, the advancing miners soon heard a different sound: deeper, earthshaking explosions. From biplanes above, tear gas, explosive powder and metal bolts rained down. “My God,” screamed one miner fighting his way up Crooked Creek Gap. “They’re bombing us!”

“They” were Sheriff Don Chafin and his deputies, who terrorized the citizens of Logan County, W.Va., by the authority of the coal companies. The miners vastly outnumbered their opponents, but Chafin had the superior position and weapons. “ACTUAL WAR IS RAGING IN LOGAN,” one local paper declared the day before.

The miners were fighting for the right to unionize, and to end the reviled “mine guard system,” a private force of armed guards who brutally enforced the company’s control in the coal fields. Unless the mine guard system was removed, John L. Lewis, president of the United Mine Workers of America, had warned, “the dove of peace” would “never make permanent abode in this stricken territory.”

On Sept. 4, federal troops arrived at Blair Mountain. The miners cheered, thinking Uncle Sam had come to liberate them from King Coal. Uncle Sam had no such plans. In 1921, about three million Americans were unemployed, and Washington was concerned that the industrial war raging in southern West Virginia could spread to other states. The troops told miners to stand down, and they did. “We wouldn’t revolt against the national government,” one of them said.

Kenneth King/West Virginia Mine Wars Museum

The miners were roundly defeated, but their struggle was not in vain: Years later, as part of the New Deal, the rights they were fighting for — including the right to collectively bargain — were written into law. Black, white and immigrant, the “Red Neck Army” (so named for the red bandannas they wore) had mounted the largest working-class uprising in U.S. history and the largest armed insurrection since the Civil War.

Today, Blair Mountain is just that: a mountain. While many battlefields are the object of exhaustive study and veneration — places and times when power wobbled and blood was shed — Blair Mountain is still largely unexplored. No statue or roadside attraction commemorates it; no tour buses roll up and disgorge visitors. Despite a burst of recent interest, for most West Virginians, the story of Blair Mountain barely even exists.

My family has lived more or less continuously in West Virginia since our patriarch, John Hinkle, settled his brood near Seneca Rocks around 1760. But I spent much of my adolescence dreaming of a world beyond the blue ridges — a dream my grandmother vigorously encouraged, having bolted over them herself when Representative Ken Hechler offered her a job in Washington. Her implied message to me, delivered via magazine clippings of girls in gaucho pants and trips to cities like Chicago, seemed to be: A much bigger world awaits. So having heard Joe Manchin call West Virginia the “extraction state,” I extracted myself. In college several states away, I majored in international relations, casting my attention as far away as I thought I should.

In the time I was gone, the mid-2000s, things back home seemed to further deteriorate. Opioid companies began flooding West Virginia with pills, and by 2010 it became the leading state for overdose deaths, kicking off a cascading crisis in the foster care system. That same year, an explosion at the Upper Big Branch coal mine killed 29 people. Since 2012, many mine operators have filed for bankruptcy. As they did, they paid astonishing sums to management while foisting much of their pension, black lung and environmental obligations onto taxpayers. By the 2020 census, West Virginia had shrunk enough to lose one of its three congressional seats, partially because people keep fleeing. It’s easy to understand why: According to one source, West Virginia is the least happy state, the worst for finding a job and the least educated. I blocked it all out, knowing I was part of the brain drain.

Then the pandemic hit, and my personal life imploded, too. Fresh off a breakup, I reluctantly retreated to my family and the hills that raised me, hoping their ancient slopes would teach me some secret about the inevitability, and gradualness, of change.

An abandoned storefront in Point Pleasant, W.Va.

Many rural places claim the title “God’s Country,” but West Virginia takes great pride in being “Almost Heaven.” Present for the monarchs on the milkweed and cascades of scarlet maple leaves that first autumn of Covid, I felt it — not for the first time, but in a way that seemed like mine. I met childhood friends at the river, clear and holy, and we blinked at each other as if discovering we were some strange species of fish, all returned to the source. As months turned to years, the idea of our previous urbane lives became laughable compared to the symphony of stars.

The longer I stayed, the more I became curious about my home. I finally wanted to know what everyone always wants to know about West Virginia: How can we be both so beautiful and so damned?

The beauty of West Virginia stretches from the northern panhandle to the Greenbrier Valley.

As I began to learn our history for what felt like the first time, the story of Blair Mountain arrived like a shocking clue. My great-grandmother, Idelene Hinkle, had been a columnist for The West Virginia Hillbilly, a satirical homage to West Virginia’s “absurd, fatalistic” humor. She had always spoken proudly of winning a Golden Horseshoe Award, a prize given to top students in West Virginia history. It seemed inconceivable that I had never heard her, or anyone else I grew up with, talk about the time West Virginia bombed its own people.

It turned out I wasn’t alone: “I am a product of the West Virginian public school system,” wrote Sam Heywood in a remarkable 2020 honors thesis at Brigham Young University, describing the pride he felt winning the same Golden Horseshoe Award my great-grandmother had. “I felt deceived when in college, halfway across the country from my home, I learned about the violent history of the Mine Wars.”

So there were two of us, then. Actually, there were far more: When Charles B. Keeney III began teaching history at Southern West Virginia Community and Technical College, most of his students hadn’t heard about the Mine Wars or Blair Mountain either, despite the fact that the battlefield lay just a few miles from campus. Professor Keeney, of course, had: He is the great-grandson of Frank Keeney, one of the towering figures of the United Mine Workers who urged his men not to let themselves be “crushed like a beetle beneath the golden chariot of the money kings.”

According to Mr. Keeney and other scholars, there is a perfectly good reason for our ignorance: Following the Battle of Blair Mountain, West Virginia kept any mention of labor conflict out of its textbooks for more than 50 years, and in many schools it is still absent.

A service road that leads to a strip mine near Blair Mountain.

It’s not just the story of Blair Mountain that the state seems to want to erase but also the soil itself. In 2009, the National Register of Historic Places, under pressure from the coal industry, delisted the Blair Mountain battlefield. This left the land open for mountaintop removal, a particularly destructive form of surface mining.

A century after the Battle of Blair Mountain, a similar war for identity and belonging is being waged. The difference, Mr. Keeney says, is that the Mine Guard System has become the Mind Guard System.

The first time I went to the State Capitol, I was on a fifth-grade field trip. “You were so excited to learn about how a bill becomes a law,” my mother recalled. “But the tour guide spent nearly the entire time talking about the gold-plated dome and chandeliers.”

Even to a child, the contrast between the lavishness of the government and the trailers that some of my classmates lived in was obvious and uncomfortable. In 2018, this incongruity became a political crisis when the Legislature took the extraordinary step of impeaching the entire State Supreme Court over their office renovations. By all measures, the renovations were grotesque: A blue suede sofa priced at $32,000 does not belong in any public office, especially not in a state where, according to the Census Bureau, the per capita income was about $29,000.

Cassady Rosenblum, a freelance journalist and West Virginia native, was the 2022-23 New York Times Opinion editing fellow. Aaron Blum is an eighth-generation Scots-Irish Appalachian from the mountains of West Virginia. He is a professor of photography at Carnegie Mellon University and West Virginia University.