American Education and the great white lies

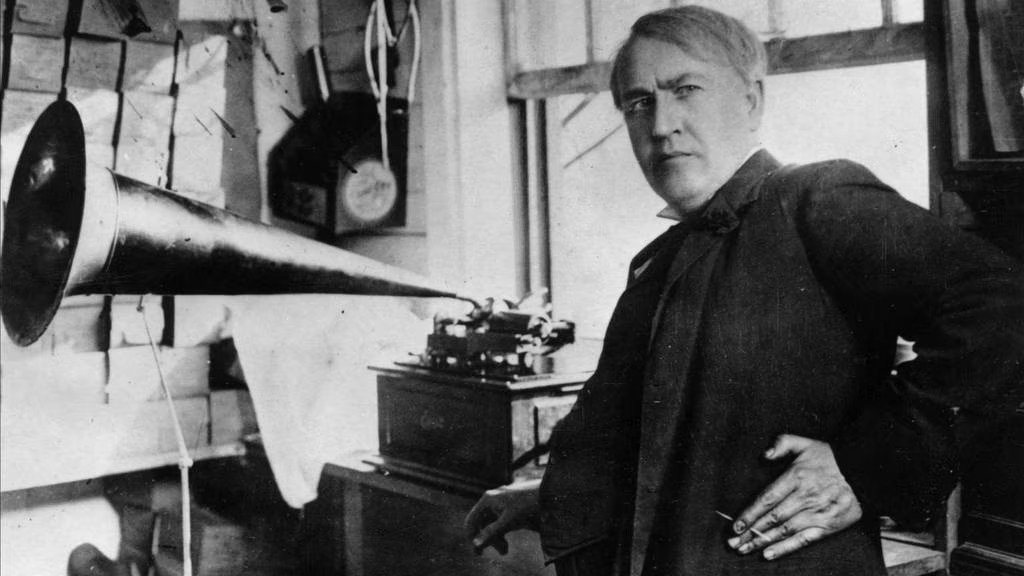

Thomas Edison's lightbulb was the culmination of experiments from other scientists and inventors. His version succeeded because it was the first commercially practical incandescent light. He continued to improve its longevity over the following decade. (Hulton Archive / Hulton Archive via Getty Images)

America’s domestic racism is only one piece of the problem of how we view history

by David Redman

Recent battles over how to teach history in American schools have focused on views of America’s domestic racism, but that’s only one piece of the problem of how we view history. Our pre-college curriculums and popular histories are filled with stories of great white men who single-handedly changed the world. This heroification, however, is often as much a made-up history as the stories of Marvel heroes in the movies. Many of these supposed ground-breakers were in fact preceded by generations of people including persons from other cultures and nations.

We’re taught that one man, James Watt, an 18th-century Scot, is responsible for steam power — but steam power was being used 2,000 years earlier in Egypt. American Thomas Edison “invented” the light bulb a century after it was in development by inventors such as Alexander Lodygin from Tambov Governorate of the Russian Empire, Italian Alessandro Cruto and the African-American inventor, Lewis Howard Latimer’s filament patents allowed for the commercialization of the light bulb. And while Alexander Graham Bell, born in Edinburgh but working in the United States, is credited with inventing the telephone, his work followed decades of work by others, such as Italian, Antonio Meucco, and the 1200-year-old acoustic telephone technology from the Chimu Culture of Peru, stored at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington.

Why does this matter? Because claiming exceptional performance only by people of Western European descent, and ignoring what non-Western Europeans have done, propagates negative attitudes toward other groups — a reality that has led to racism, anti-immigrant sentiments and white supremacy.

Arguably the most problematic of these ethnocentric myths involves what’s often called the most important invention of the last millennium: the celebration of Germany’s Johannes Gutenberg as the inventor of movable metal type. Historians often say that Gutenberg’s mid-15th century invention led to some of the most important changes in western history — including the Protestant Reformation, nationalism, capitalism, individualism and democracy. Gutenberg, we’re told, was one of the most influential people in human history because of the movable metal print he invented.

It was an incredible achievement, in that telling.

But it’s not true.

In 1377, about two decades before Gutenberg was born, an anthology of Buddhist teachings was printed in Korea with movable metal type. This book, “Baegun hwasang chorok buljo jikji simche yojeol” — often known as “Jikji” — was recognized by UNESCO as the oldest extant movable metal print book in 2001, though few people have yet heard of it. In fact, in 2013, when I visited the French National Library to apply to see this ancient artifact, none of the staff I encountered knew anything about it.

Eventually, they discovered on their intranet system that “Jikji” was locked away in a basement vault in the old Richelieu branch in central Paris. The fact that this first-ever movable metal print book was hidden in this major Western institution spurred me to make the 2017 documentary “Dancing with Jikji,” which explores Eurocentrism and early print history. The French National Library wouldn’t cooperate with us or allow us to film the book, which remained concealed in the library’s basement vault.

This summer, though, the library finally displayed “Jikji” at an exhibition on early print. I was excited to hear about this development — figuring the book would receive some well-deserved attention — until I read the title of the exhibit: “Printing! Gutenberg’s Europe.” How, I wondered, could Gutenberg remain so much the star that there would be no mention of “Jikji” in the title?

Once people look into the history of movable metal print in 13th century Korea, some still rationalize Gutenberg’s celebrity by arguing that his invention was made independently; Korea was just too far to have had influence. But in fact, there were dynamic exchanges of goods and culture along the Silk Road for millennia, especially between the 12th and 14th centuries. At a conference in Seoul in 2005, Al Gore told the story of Christian monks returning to Europe from Korea with samples of movable metal print, which they gave to Gutenberg. Our film revealed a 14th-century letter, in which Pope John XXII thanks the King of Korea for welcoming monks into Korea prior to 1333. The letter, held by the Vatican Secret Archives, gives some inconvenient proof to those who deny the possibility that Al Gore’s story may have merit.

There is no longer an excuse for not promoting a more inclusive and expansive history and disrupting this Eurocentric view of the world. That means not only recognizing Korean technology in this instance, but also acknowledging that such inventions were multinational, intercultural and often multi-century developments. The print technology that changed the world was a venture of resourceful people across continents, building and remaking the devices that eventually changed how humans recorded and disseminated information.

We will not be able to stamp out the misguided white nationalist movement that is disrupting society in America and elsewhere until we recognize a history that reflects our interconnectedness — not a fabricated Eurocentric worldview and the fables of a few great white men.